You know that satisfying feeling when you see fresh asphalt being laid and a massive roller smoothing it out? There’s something oddly mesmerizing about it. But have you ever stopped to wonder what’s actually going on under those huge drums? Let’s dig into it.

So What’s the Deal with Steam Rollers Anyway?

Here’s a Fun Fact

Most of them are called steamrollers by common people but if we are to be honest- almost none of them use steam as their energy sources. The term comes from the 1860s when they actually burnt coal to heat water and produce steam. Though today, these are powered by diesel or even electricity. However, the word ‘steam roller‘ sounds much better than ‘diesel-powered compaction vehicle,’ so people kept using it.

What These Machines Actually Do

Basically, their work is quite simple when analyzed:

- They dirt down loose materials like earth, stones, and that hot asphalt you might have seen on roads

- All these small air chambers? They are eliminated. Crushed.

- The uneven surface is pressed in such a way that it becomes smooth enough for vehicles to drive on

- The material becomes much denser, which also implies that it won’t sink or crack later on

- The binding of everything takes place under all that pressure

We’re Talking Serious Weight Here

These aren’t just any machines. Their weight span is quite diverse:

- Tiny ones for the likes of driveways and side projects? Around 1-3 tons perhaps

- Most rollers used for residential street? The weight is probably between 3 and 8 tons

- Large works on highways? There is a heavy weight of 8-20 tons, sometimes even more, is considered here

- There are occasions when certain rollers reach 25+ tons if fully loaded

The earth is being pressed by a sizable amount of metal.

Why Does Heavy, Better for Road Building?

The Basic Physics

Weight and pressure are often confused, however, they are not the same things. Weight is the force that gravity exerts on an object. Pressure is that weight focused on a smaller area.

Imagine that you are at the beach and you put your hand on the sand, not much change would be visible. Now if you do the same thing but with your fingertip only, you will be sinking in the sand. That is the difference.

The insufflation of a 4-foot drum by a 10-ton roller produces a very high pressure. This pressure opens the Pandora’s box:

- It pushes the air which is between the small particles out

- It forces the particles to be closer so that they interlock

- It makes the material much denser

- All of a sudden the surface is able to take on traffic

What’s Going On During Compaction

When that drum rolls over loose material, a bunch of stuff happens at once:

- The concrete mix in the compaction layer is refined due to the decrease in air voids from around 5-8% to just 2-3%

- The particles that were previously separated by air voids are for most part touching and thereby interlocking with each other

- The strengthening effect is going to be in the range of several hundred percent, say from 300 to 500%

- Since water is prevented from entering the structure thus formed, damage is good part of the way avoided

- The whole thing has become capable of carrying even heavy trucks without disintegrating

Pretty neat when you think about it.

Breaking Down the Parts: What Makes These Things Tick

Those Massive Drums

Those Massive Drums

This is where the magic happens. Those giant steel cylinders you see doing all the work.

Different Setups You’ll See:

- One can find a single-drum model with that drum being in the front and normal tires used for the rear—a quite versatile vehicle

- Models with two drums, one in front and one in back, are used for higher compaction.

- After that, there are the three-wheelers, which have one large drum at the back and two smaller ones at the front for working in tight areas

What Makes the Drums Special:

- Their diameter is most often between 3-5 feet

- Their width is not usually more than 7 feet, if also less than 3 depends on the type of work

- The working surface is metal, but at times they put a layer of some material between the steel and the surface for special cases

- Would you believe it? They can do the filling of these things with water or sand in order to add up to 5 tons of weight to the drum instantly

The Engine Situation

Back in the Day (1860s Through the 1950s):

If you were a guy who worked these machines back then, your life certainly wasn’t easy. The onus was on you to work a shovel full of coal into the firebox while at the same time you kept an eye on the gauges to make sure the whole thing would not go out of control. The whole process of warming up the machine and loading it with coal took approximately 30-45 minutes, during which one had to keep on adding the fuel and keep an eye on the gauges. Oh, and did I mention the place was hot, dirty, and generally a nightmare of a job?

Modern Stuff:

Now things are much simpler. Typically, the diesel engines (50-150 horsepower) are linked to hydraulic systems which in turn operate everything. You have smooth speed control and instant start-up, and it is by far a cleaner process. The operator is in a cab with controls resembling those of any other heavy machinery.

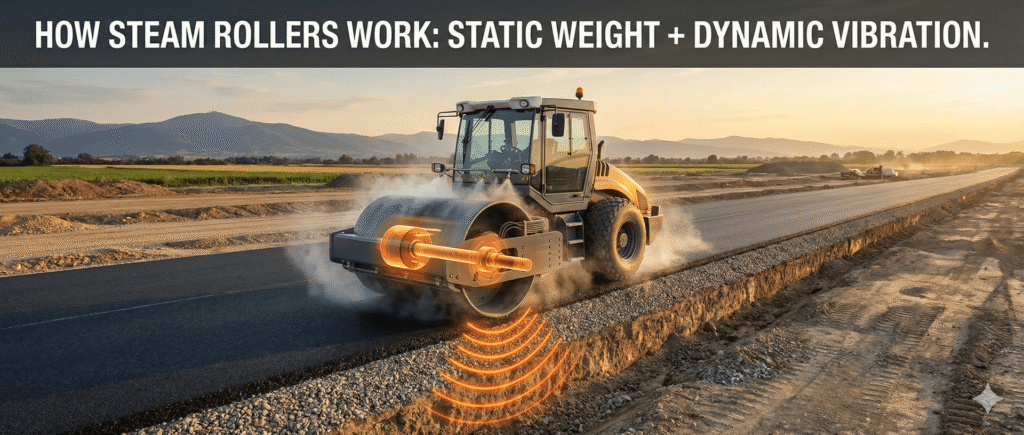

The Vibration Thing—This Changed Everything

Okay, this is where modern rollers really step up their game. They’ve got this mechanism inside the drum that makes it vibrate like crazy.

How It Works:

- Most of the time, the spinning drum has some off-center weights that rotate very fast around the drum

- As a matter of fact, the number of revolutions per minute is between 2,000 and 4,000

- On each vibration, the drum is actually lifted a little bit, and then gravity throws it back down

- Therefore, it is like thousands of tiny hammer blows happening every minute

Why Bother with Vibration?

- By using a vibration device, the number of passes you need to make may be cut from 8-10 to only 3-5

- The depth of the compaction becomes way greater—like 30-50% more

- It also works very well on gravel and materials of the same kind

- Besides time, a great deal of fuel is also saved

When Vibration Is Not Desired:

- Final passes on asphalt—ripples will be created in the surface

- Anywhere near underground pipes or utilities

- Thin layers of asphalt may develop cracks

- Near buildings in which the vibration may cause damage

The Water Sprayer Setup

You’ve probably noticed rollers constantly spraying water. That’s not just for show.

Reasons:

- Asphalt heated to a very high temperature really wants to stay tightly attached to the metal drum

- Water ensures the drum doesn’t get too hot and also serves as a barrier

- Stops the process of the material building up and thus making bumps

- Is drilling the longest life-time way of the drum

Elements:

- A container of 50-200 gallons, or maybe even more

- Spray bars located right in front of the rollers

- The pumping system which you are allowed to regulate

- Certain crews put soap in along with a special release agent to make the process go more smoothly

Different Rollers for Different Jobs

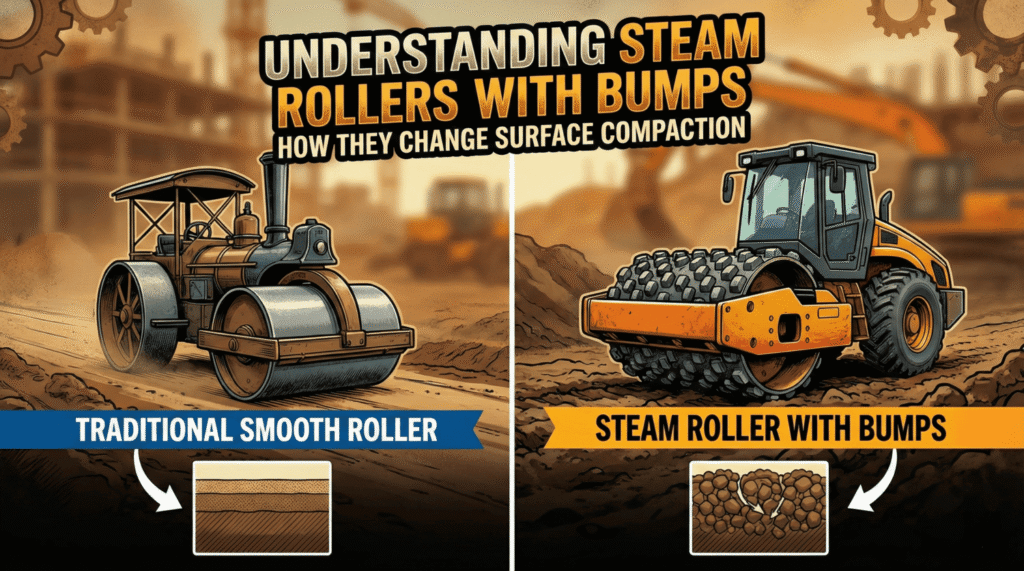

Static Rollers (Just Pure Weight)

Where They Shine:

- The last few passes of an asphalt paving to make it really smooth

- Checking how strong the sub-base is

- Very thin areas where vibration could cause damage

- Achieving the correct grain

The Good Stuff:

- They are the ultimate for smoothness

- There is no danger of overdoing it

- They are quieter to operate

- Lower initial investment

The Downside:

- More passes will be required to complete the work

- Not very good for gravel and rocks

- It takes longer overall

Vibratory Rollers (The Workhorses)

What They Are Most Effective For:

- Base layers that require deep compaction

- Gravel, crushed rock, and basically any granular material

- Heavy/multiple asphalt layers

- Almost any large-scale road project

The Figures:

- Vibration height: 0.3-2.0mm

- Speed: 2,000-4,000 vibrations per minute

- Force generated: from 5 to 30 tons depending on the size

Different Modes:

- High amplitude/low frequency when going deep

- Low amplitude/high frequency for working the surface

- Static mode

Pneumatic Rollers (The Smooth Operators)

The Design:

- Seven to thirteen rubber tires replace the steel drums

- The tires are arranged in two rows that are overlapping

- Can be brought up to 200 tons with weights for very large jobs

How They’re Different:

- The rubber tires make this kneading action

- Compacts in a different way than steel

- Closes the surface very well

- Nice texture on the final product

When to Use Them:

- Last layer of compaction on asphalt

- Airport runways where the surface has to be very smooth

- Parking areas

- Is normally followed by a steel drum roller for the best result

Sheepsfoot Rollers (For Dirt Work)

The Weird Design:

- Drums that are covered with these protruding pegs or “feet”

- The feet can protrude 8-12 inches

- It is stomping more than rolling because the action is created

Where You See Them:

- Clay and fine soils

- Dam and embankments construction

- Foundation pads

- Landfill compaction

How They Operate:

- Those feet go deep into the loose material

- They compact layer by layer from the bottom up

- The feet gradually remain on the surface as the material becomes denser—they call it “walking out”

Combination Rollers (Best of Both Worlds)

What They’ve Got:

- One end has a steel drum while the other is fitted with rubber tires

- Obtain both kinds of consolidation in one operation

- Have the option to vary the weight depending on the condition

Who Employs Them:

- Those contractors of a smaller scale that are unable to afford several machines

- Works with a great deal of variation

- Situations where budget is limited

- Residential and small scale commercial jobs

How the Actual Process Works

Step One: Breakdown Rolling

What’s Happening:

- First couple passes over the fresh material

- Asphalt’s still super hot—like 300°F or hotter

- Usually using lighter to medium rollers

- Vibration’s cranked up to full blast

The Goal:

- Get it up to about 80-85% density right off the bat

- Knock out the big air pockets

- Create something stable for the next passes

- Do it fast while everything’s still hot and workable

How Many Times? Usually 2-3 passes over the same spot

Step Two: Intermediate Compaction

What’s Happening:

- Might bring in heavier rollers now

- Vibration’s at medium settings

- Material’s cooling down but still workable—maybe 200-250°F

The Goal:

- Push density up to 90-92%

- This is where most of the real compaction happens

- Make sure it’s compressed all the way down, not just on top

- Check for any soft spots or weird areas

How Many Times? Another 3-4 passes

Step Three: Finish Rolling

What’s Happening:

- Vibration gets turned OFF for these final passes

- Just static rolling now

- Material’s cooled quite a bit—around 150-200°F

- All about making it look good now

The Goal:

- Hit that final target density—usually 92-96%

- Get rid of any marks or texture from the roller

- Create a smooth, sealed surface

- Time for quality checks

How Many Times? 2-3 final passes should do it

Temperature Matters More Than You’d Think

Getting It Right:

- Too hot: the material just pushes around under the roller

- Too cold: it won’t compact and might even crack

- The sweet spot: compacts easily and stays where you put it

The Compaction Window:

- For asphalt, you’ve got between 300°F and 175°F to work with

- That usually gives you 15-45 minutes depending on conditions

- Cold day? That window shrinks fast

- Hot day? Wider window, but it might be too soft at first

Things That Mess with Your Timing:

- Outside temperature makes a huge difference

- Wind can cool things down 50% faster

- How hot the base is underneath matters

- Thicker layers stay workable longer

Making Sure It’s Done Right

How They Test It

Nuclear Density Gauge:

- Uses radioactive material to measure how dense everything is

- Gives you readings instantly

- Can check multiple depths

- Pretty much the standard in the industry

Core Sampling:

- They literally drill out chunks and test them in a lab

- Most accurate way to do it

- Used to double-check those nuclear gauge numbers

- Required on a lot of big projects

Proof Rolling:

- Drive a loaded truck over the compacted area

- Tests if it can actually handle weight

- Easy to spot soft areas

- Simple but it works

What They’re Looking For

The Targets:

- Asphalt needs to hit 92-96% of maximum theoretical density

- Base materials: 95-98% of standard Proctor density

- Dirt subgrade: 90-95% of max density

What Happens If They Mess Up:

- Roads start getting ruts and dips way too early

- Cracks show up faster

- Water gets in and causes even more damage

- The whole road might only last half as long as it should

Best Practices

The Pattern:

- Start at the edges, work your way to the middle

- Overlap each pass by 6-12 inches so you don’t miss spots

- Keep a steady speed—usually 2-5 mph

- Don’t stop suddenly on hot material or you’ll leave marks

Speed Matters:

- Go slower and you get more compaction per pass

- Too slow though, and you might push material around

- Too fast and there’s not enough time for it to work

- Adjust based on what you’re working with

When Things Go Wrong:

Asphalt Sticking to the Drum:

- Turn up the water spray

- Check if something’s clogged

- Maybe add some release agent

- Make sure the drum isn’t overheating

Uneven Results:

- Are you overlapping consistently?

- Check if the weight’s distributed evenly

- Look for wear or damage on the drums

- Maybe adjust those vibration settings

Material Cracking:

- Probably too cold to compact properly

- Try reducing the vibration

- Switch to a lighter roller or turn off vibration

- Could be the wrong mix—worth checking

How We Got Here: The History Stuff

The Steam Era (1860s-1950s)

The Beginning:

- First ones showed up in France and England

- Completely changed how roads got built

- Replaced horses pulling stone rollers

- Could do in hours what used to take weeks

What It Was Like:

- You needed a fireman and an operator working together

- Had to have coal and water on site

- Top speed: maybe 2-4 mph

- Once it was heated up, you could keep going all day

Classic Models People Remember:

- Aveling & Porter from Britain

- Buffalo Springfield from America

- You can still see working ones at shows and museums

The Changeover (1930s-1960s)

Diesel Shows Up:

- More convenient than dealing with steam

- Could start up and shut down way faster

- Cleaner to operate

- Cost less to run

Why It Took Time:

- Operators liked what they knew

- Early diesel versions weren’t super reliable

- Took decades to fully switch over

- Last steam rollers were built in the 1950s

Modern Times (1970s to Now)

Game Changers:

Vibration (1970s):

- Literally doubled how fast you could compact

- Used way less fuel

- Projects finished in half the time

Computers (1990s):

- Automated a lot of the adjustments

- Could monitor everything digitally

- Made displays way easier to read

GPS and Smart Tech (2000s):

- Real-time maps showing density

- Counts passes automatically

- Documents everything for inspectors

- Prevents overdoing it or missing spots

Today (2020s):

- Electric and hybrid engines showing up

- Some can operate themselves

- Sensors everywhere giving feedback

- Remote monitoring from the office

Keeping These Things Running

Daily Stuff

- Check the drums for damage or buildup

- Make sure hydraulic fluid’s topped off

- Test that water spray system

- Verify vibration’s working right

- Check tire pressure if it’s got tires

Weekly Tasks

- Grease everything—there’s usually 10-20 spots

- Look at belts and hoses for wear

- Clean out air filters

- Check bearings in the drums

- Make sure all the bolts are tight

Bigger Maintenance

- Change oil and filters monthly or seasonally

- Deep dive on the hydraulic system

- Check those eccentric weights in the drum

- Test all the safety stuff

- Make sure it’s still compacting properly

What Breaks Most Often

Parts You’ll Replace:

- Water spray nozzles—they clog all the time

- Drum scrapers that clean material off

- Hydraulic hoses and seals

- Bearings in the vibration system

- Rubber pads and mounts

What It Costs:

- Resurfacing a drum: $5,000-15,000

- Rebuilding vibration system: $10,000-25,000

- Engine overhaul: $15,000-40,000

- Brand new machine: anywhere from $50,000 to $300,000+

Safety and Environmental Stuff

Environmental Impact

Noise:

- Usually running at 85-95 decibels

- Vibration mode can hit 100+ dB

- Operators need hearing protection

- Can definitely bug nearby neighbors

Emissions:

- Newer diesel engines are way cleaner now

- Electric ones available for indoor work

- Burns about 2-8 gallons per hour

- Most have idle reduction to save fuel

Safety Requirements

Who Can Operate:

- Need heavy equipment certification

- Requires hands-on training

- Gotta understand how compaction works

- Be aware of what’s dangerous on site

Safety Features:

- Rollover protection built in

- Backup alarms and cameras

- Emergency stop buttons

- High-visibility paint and markings

- Protection from falling objects

On the Job Site:

- Keep workers away from the compaction zone

- Watch out for underground utilities

- Stay back from edges

- Use spotters when backing up

Random Facts

Stuff You Might Not Know

- The biggest roller in the world weighs over 200 tons—it’s for airport runways

- There are actually steam roller festivals where enthusiasts parade vintage machines around

- Some rollers can compact 3 feet deep with vibration

- The ancient Romans used stone rollers pulled by slaves for their roads

- Modern GPS-equipped rollers know exactly where they’ve been

- A single roller can compact a quarter mile of road in a day

- Renting a big roller can cost over $1,000 a day

- You can actually see the vibration pattern when they take core samples later

- Some have heated drums for working in freezing weather

- Airport rollers sometimes weigh more than the planes that’ll land there

Record Breakers

- Heaviest: 200+ tons when fully ballasted

- Oldest working steam roller: Several from the 1870s still run

- Fastest compaction: Modern smart systems finish highways in half the time

- Most expensive: Specialized ones for major projects can hit $500,000 or more

What’s Coming Next

New Technology on the Horizon

Self-Driving Rollers:

- GPS guides them through programmed patterns

- Saves on labor costs

- Gets consistent, optimal compaction every time

- Could run 24/7 if needed

Real-Time Quality Checks:

- Measures density constantly as it moves

- Gives instant feedback to the operator

- Automatically adjusts settings

- Documents everything for inspectors automatically

Electric and Hybrid Power:

- Zero emissions for indoor or sensitive areas

- Way quieter operation

- Lower fuel costs over time

- Some even have regenerative braking

Smart Material Integration:

- Sensors that talk to “smart” asphalt

- Adapts to temperature automatically

- Sets itself based on the material

- Predicts maintenance needs before breakdowns

The Challenges

- Training people to use all this complex new tech

- Balancing automation with keeping people employed

- Making sure electronics stay reliable in harsh conditions

- Managing all the data these smart systems create

- Updating industry standards for new technology

Wrapping It Up

Look, steam rollers aren’t flashy. They don’t get a lot of attention. But every single mile of highway you drive on, every parking lot, every airport runway—all of it depends on these machines doing their job right.

From those coal-burning monsters in the 1800s to today’s GPS-guided, computer-controlled beasts, the basic idea hasn’t changed: apply a massive amount of weight in a controlled way, and you turn loose material into solid infrastructure that’ll last for decades.

Next time you’re cruising down a smooth highway, take a second to appreciate the roller operators who made it happen. They’re out there in all kinds of weather, making methodical passes back and forth, building the literal foundation of how we all get around.

That’s what steam rollers really do: they turn temporary into permanent, loose into solid, and make the impossible into the everyday roads we all take for granted.